When Ola* was born, 21 months ago in Mtwara Region, South-eastern Tanzania, his parents looked forward to grooming a healthy baby boy. But amid the aura of joy and high hopes, one thing appeared just not right. The newborn baby had a high-pitched voice when breathing, prompting health concerns. The parents, however, had no clue that the baby’s breathing condition was the beginning of a lifetime situation that they would have to contend with.

Since then, the father, Mr. Diallo*, embarked on the search for a cure of his boy’s condition–going the proverbial extra mile to take him to hospitals in the country’s biggest commercial capital: Dar es-Salaam. That was June 2021. And that’s when doctors revealed to Diallo that his son, Ola, was actually suffering from a genetic disorder known as Down Syndrome.

Diallo had never heard of such a condition. The news left him perplexed. He started digging through the internet, only to learn about yet another heartbreaking story. He stumbled on information which indicated that society had in fact labelled the children with Down Syndrome as ‘ndondocha’ or ‘zezeta’-such degrading names.

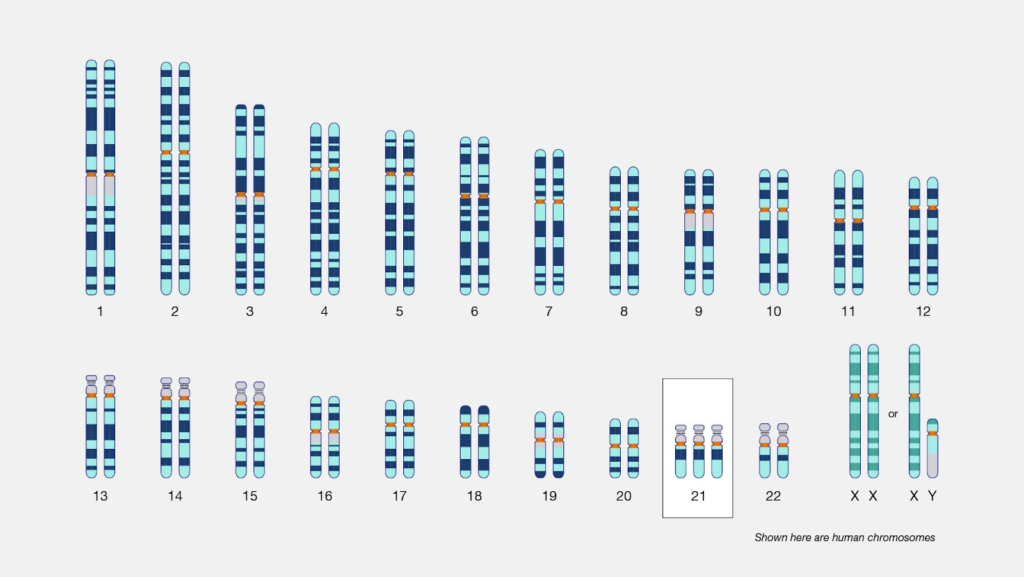

To understand Down Syndrome, it’s important to remember that a human being is made up of building blocks known as cells which have a structure at the centre known as the nucleus. Within the nucleus, there is a structure called a chromosome which carries long pieces of DNA–the genetic information that determines how your body is made. It’s the chromosome that we’ll talk about here as we explain what Down Syndrome is.

Normally, each cell in the human body has 23 pairs of chromosomes. A person with Down Syndrome gets an extra chromosome, usually by chance because of changes in the egg or sperm before the person is born. So, one gets three copies of chromosome number 21 instead of the usual two. This affects the development of a child born with this condition–and that’s exactly what happened to Diallo’s son, Ola.

It’s because of this number that 21st March was selected to commemorate World Down Syndrome Day. The condition is fairly common around the world and chances for a child to be born with it are equal for all regions. It can occur in people of all races.

Causes and risk factors

Other than knowing that Down Syndrome occurs in people with an extra chromosome, there is no definitive research that indicates the condition occurs or what factors could be at play.

Women aged 35 and older have a higher chance to conceive a pregnancy affected by Down Syndrome than women who conceive at a younger age. However due to higher birth rates in the younger population, the incidence of Down Syndrome is higher among children born to women under 35 years of age.

People with the condition usually have a flat face, almond-shaped eyes and a short neck. Their hands and feet are small and they have loose joints and poor muscle tone. In addition to this, they may exhibit other health problems including deafness, sleep apnea, ear infections, eye diseases and congenital heart defects.

Facing the reality

When doctors finally revealed to Diallo that his child had Down Syndrome, he recalls that it wasn’t easy for his family to accept that reality. His wife was stressed about the situation and the whole family was in denial. This difficulty was compounded by the fear of losing their child, triggered by widespread online information which indicated that children with this condition usually die when still young.

The parents desperately moved from doctor to doctor in pursuit of a solution to their baby’s health problem, a situation that would force them to start from afresh whenever they met a new expert. This was very challenging for Diallo and his family. Consequently, they opted for a private hospital where they would be attended with the same doctor each time.

Things changed with time. Ola was subjected to medical checkups to rule out if he had other defects. This went along with counselling sessions for the parents.

Life-changing experience

The diagnosis has changed Diallo’s lifestyle in many ways, especially when the baby was still a newborn. In the early days, the baby needed constant attention-more so during the night. So, Diallo would wake up every hour to check on the baby.

Like any parent, Diallo had expectations for a healthy baby but life turned out differently from the start. They have more hospital visits than average. Ola is growing slower than other children and still can not talk or walk. He experiences mood swings and has difficulty interacting with others. So the parents have had to get creative to make sure he gets a normal life as much as possible.

One of the things that have improved Ola’s life and ability to interact was to change his environment by enrolling him in a daycare centre. He now laughs and plays more, makes funny voices and has learnt to eat. Ola is now a playful, outgoing and proactive boy. Although he is not growing as fast as the other kids, he is equally charming and eager to learn.

The biggest challenge for Diallo has been the lack of reliable information on Down Syndrome and the absence of special facilities or clinics dedicated for children with the condition. He is aware that his child is different and has special needs but information and resources have been a setback. Having to meet new practitioners everytime, each with their own treatment plan is a scare for him.

In terms of patient support groups, he heard about only one such organisation but later found it was inactive. When asked what he would tell a parent that just found out their baby has Down Syndrome, he says, “First accept the diagnosis and secondly, let the child grow.”

That is the best advice he ever received, which learnt from a doctor at Muhimbili National Hospital. He also advises other parents to understand that they will need to teach the child to interact with others and let them grow as slowly as they need to. Most importantly, he says, it is important to surround the children with love.

He recommends that the government establish special facilities or clinics that would only focus on Down Syndrome to improve health outcomes and livelihood.

The situation in Tanzania

Down Syndrome in Tanzania is a topic that has recently received attention but the lack of public awareness about it is still rife. This is also reflected in the fact that there is no word for Down syndrome in Kiswahili, the predominant language spoken in the country and Africa. People with the condition have to endure stigma, with children being labelled by words that translate to ‘retard’ or ‘zombie’.

As it is with other developing countries, children with Down Syndrome and their parents are subjected to many forms of stigma in Tanzania. Fathers abandon their families and some people believe parents are being punished by God for sacrificing their children’s perfect mental abilities for riches. The stigma has forced parents to keep their children indoors, depriving them of a normal life and inclusion in society.

Children with Down Syndrome also face a number of challenges including difficulty in accessing education since they are considered as incapable of learning in a normal school environment while there is an absence of user-friendly systems to accommodate their needs. Financial challenges are also common because a lot of money is spent to cater for their medical needs.

How to diagnose the condition

Down Syndrome can be tested during pregnancy or after a baby is born. There are two basic types of tests for the condition during pregnancy:

- Prenatal screening tests that often include a combination of blood tests and an ultrasound to show if there is a chance for the unborn baby to have Down Syndrome.

- Prenatal diagnostic tests that are performed after a positive screening test to confirm or rule out a diagnosis of Down Syndrome. They examine the placenta, amniotic fluid and blood to look for changes in the chromosomes that could indicate the diagnosis. Such tests include chorionic villus sampling, amniocentesis and percutaneous umbilical blood sampling.

After a baby is born, a diagnosis can be made based on physical signs and a karyotype genetic test can be used to confirm diagnosis.

Treatment

Down Syndrome is a lifelong condition and there is no cure for it. Treatments and supportive services are provided based on an individual’s physical and intellectual needs, strengths and limitations. Interventions such as speech, occupational and physical therapy help children with Down Syndrome develop to their full potential. They may require regular medical consultations due to other health problems and birth defects.

Way forward

Currently there is no data describing the extent of the problem, making devising intervention strategies difficult.

Down Syndrome is not a mental defect but rather a genetic condition that interferes with the baby’s normal development. Each person with Down Syndrome has a right to be included in society dynamics since they all have unique talents, skills and ability to thrive.

Since more public education and awareness is needed to raise awareness, it is imperative that people are educated on Down Syndrome in order to eradicate the stigma around it and improve outcomes among children with the condition. User-friendly systems should be put in place to ensure people with Down’s syndrome in Tanzania receive fair treatment in the education, health and socio-economic sector. Importantly, research is needed to understand patterns, diagnosis and treatment options for Down Syndrome in Tanzania. Last but not least, the role of patient advocacy groups is very key. Pearl of People with Down Syndrome Foundation is one of such organisations in Tanzania that advocates sustainable inclusion rights for people with Down Syndrome.

*Not their real names

The co-author of this article is Aneth David (PhD), a biotechnologist and a member of the executive committee, Tanzania Human Genetics Organization (THGO)