Imagine a seemingly ordinary sore throat, the kind that you may have experienced during cold seasons. You’ve perhaps relieved the itchiness with a pill or two, swallowed with a glass of water. But for some, these sore throats can lead to serious complications. In East Africa, one in seven people suffers from a fatal condition that may have begun with itchy throats they had as children. The condition is known as Rheumatic Heart Disease (RHD), and it kills over 288,348 people each year globally, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

RHD is a “process,” that is “characterized by damage to the heart valves,” explains Dr. Emmy Okello, Chief of Cardiology at the Uganda Heart Institute, who spoke at a recent Pan-African Society of Cardiology (PASCAR) Rheumatic Heart Disease Task Force Webinar for African Journalists.

The process

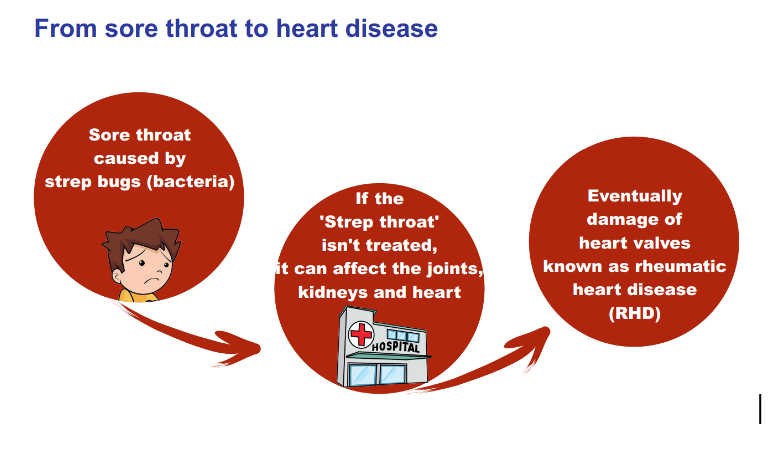

RHD starts with an infection of a bacterium called Streptococcus pyogenes which causes sore throats and related conditions. When not properly treated or when a person gets repeated infections, the bacteria can cause the body’s defense system to react and lead to scarring of the heart valves. This condition is known as Acute Rheumatic Fever (ARF).

Over time, ARF damages the heart valves, giving rise to RHD. It’s some sort of chain reaction, starting with that seemingly harmless sore throat. Rheumatic fever is a wake-up call that someone is at risk of this neglected but deadly heart disease.

ARF is rarely detected during childhood in most African health facilities, according to Dr. Okello, who is also the chair of a task force on RHD at the Pan-African Society of Cardiology (PASCAR).

He cites an example of South Africa and Uganda, which have the largest registries of the disease, with most patients being diagnosed late when the complications are already severe.

This, he says, results in millions of Africans between the ages of 20 and 25 dying from RHD each year if they do not undergo expensive surgery to replace their damaged heart valves.

Reversible if diagnosed early

“We need to actively look for them (children with repetitive sore throats and ARF symptoms) and save them from dying,” says Okello, further explaining that before assisting those with RHD, “…[society] must understand what it means to live and die with the condition.”

Where poverty is widespread

The impact of RHD can be felt in many villages where there is only one teacher for every 100 pupils, classrooms are overcrowded, the dispensary is no better and the waiting line to see the doctor is too long. A child finally gets home and is greeted by cramped huts with poor ventilation, where people live with 26 extended family members. It’s a harsh reality that over 14 million Tanzanians live in poverty, according to the World Bank.

The uncomfortable truth.

Children aged up to 10 live in typical villages where malaria is common and antibiotics are scarce. Take this of a child who gets a sore throat but whose parents don’t take him/her to the health worker because they think it’s just malaria. But when they ultimately make a decision to go to the facility, a health worker in the village only offers common over-the-counter painkillers to simply relieve pain.

In this alternate universe, the condition worsens. Eventually, the child is diagnosed with Acute Rheumatic Fever later at a city hospital, after a series of referrals. Initiatives to help tackle this problem do exist but there is a pressing need to scale up further interventions.

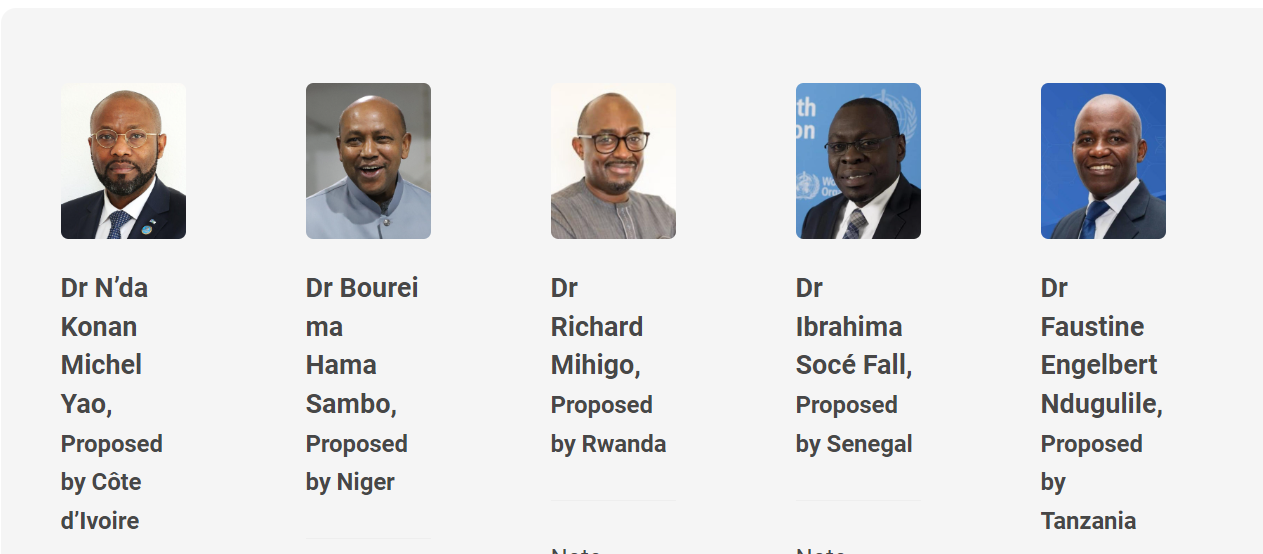

Since 2016, PASCAR, which works to improve heart health and reduce cardiovascular disease in Africa, has been running a free RHD diagnosis campaign, helping patients stay alive with daily penicillin injections. The Society has reached over 100,000 children and adolescents so far.

Much more needed…

Is it important to think about those who might have missed the opportunity for a diagnosis. They’ll continue with life as usual until they get older and realize their heart isn’t what it used to be. By then, it will be too late.

To put it another way, overcrowding in schools, hospitals, and homes makes it easier for the bacteria that cause acute rheumatic fever (ARF) to spread, which in turn increases the risk of developing RHD.

The economic burden of this neglected heart disease places on families and communities is substantial. Young adults with RHD face an uncertain future. They must undergo expensive surgeries and live with the consequences of reduced productivity until their untimely deaths.

Where is the solution?

Primary prevention revolves around enhancing socioeconomic conditions and access to healthcare. Promoting vaccine development is equally critical.

Professor Pilly Chillo of the Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) says, “People who get ARF are special.”

Only 3% of the population reacts to rheumatic fever. That doesn’t make the disease any less significant. Prof. Chillo insists that children showing chest and joint pains, fast heart rates, and other symptoms of ARF should be on antibiotics for the rest of their lives. It will cost them a couple of dollars per month.

“Whenever people who are susceptible to ARF come into contact with the bacteria they react to it, and this can eventually lead to damaged heart valves and rheumatic heart disease.” Unfortunately, many children with ARF symptoms are misdiagnosed and treated for malaria at primary healthcare facilities in Tanzania and across Africa.

We can do better.

The first step to fighting RHD is to catch it early when it is still reversible. RHD begins as an infection (sore throat or mild fever) and ends as a non-communicable disease (NCD). This dual nature of RHD poses a challenge for policymakers and researchers in Tanzania.

For example, Professor Chillo points out that there is a lack of burden-of-disease data for RHD in Tanzania. The true scope of the problem is unknown, although a recent study showed that 2.1% of school-going children have been exposed to the bacteria that causes rheumatic fever. Not all of these children will develop complications, but some will go on to develop full-blown RHD as adults.

She emphasizes that the best way to diagnose rheumatic heart disease (RHD) early is to “do what we did for malaria and HIV/AIDS.

“We cannot wait for improved socio-economic conditions, which are largely dependent on politics rather than researchers. Instead, stakeholders must sensitize primary healthcare workers to check for GAS bacteria through public awareness campaigns.”

For public and private hospitals, health information systems should be routinely analyzed for data patterns that suggest rheumatic fever. School-based RHD control programs are also essential for increasing community awareness and knowledge of GAS, rheumatic fever, and RHD. This is primary prevention making everyone aware of this silent killer.

In addition, monthly penicillin injections are critical for children and young adults who have already been diagnosed with the precursors to RHD. This is known as secondary prevention. The government should also fund surgery for complicated cases to ensure the success of tertiary prevention. Treating people with RHD with medication and surgery can help replace damaged heart valves.

But, as with any solution, there are limitations. Current RHD diagnostic criteria are outdated and ineffective, leading to missed cases. To improve prevention and diagnosis, we need to increase awareness among healthcare workers and the public. Another option is to develop better lab tests for rheumatic fever and make healthcare more accessible. Nevertheless, the best way to prevent RHD is to develop a vaccine for Group A Streptococcus (GAS), the bacteria that causes it. The World Health Organization is already working to make this happen.

Remember, the progression of RHD involves three key stages. Initially, a child acquires a GAS infection, also known as Strep A, from a rapidly spreading bacteria common in crowded environments. During this stage, the condition remains reversible. Thanks to relatively cheap antibiotics. However, many children do not receive prompt treatment, and the infection can progress to the next stage. Acute rheumatic fever can develop after repeated Streptococcus infections. Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) develops when the heart valves are eventually damaged. It is irreversible.

“The process of rheumatic heart disease starts in childhood and appears when they are returning home from college or entering the workforce,”

“We must prevent the disease from affecting more people,” Prof. Chillo emphasizes.