A social media post went viral on WhatsApp recently, leaving people wondering if oral HIV-self testing kits are now commercially available in pharmacies across Tanzania. Not many people were able to explain the post, not even the medics—except a few who are privy to HIV programs.

Before delving into details, it’s important to recall that in Tanzania, only 52 percent of adults aged 15-64 are diagnosed and aware of their HIV status. Self-testing, therefore, could be a way to boost the testing coverage in communities and accelerate the goal of controlling the epidemic in Tanzania by 2030.

But “How will this work?” was the first question upon seeing the social media post, prompting a short visit at a popular community pharmacy in Mwenge suburb, Dar es Salaam. Arrival at the pharmacy confirmed the same message. At the entrance, a roll-up banner displays the Swahili message: Sasa naweza kujipima VVU mwenyewe translated unofficially as “Now I can test myself for HIV.”

Here’s what happened…

Inside the pharmacy, a drug dispenser is ready to serve you, just like any other client if you need the kit. But before s/he can provide the kit, you will have to submit your name, age and phone number. You won’t, however, be required to show an ID to verify any of the details you provide. Perhaps at other pharmacies they could be stricter with details.

“Your particulars are important for authorities to follow up,” the seemingly busy dispenser intoned, and went to the rear chamber of the pharmacy to collect the kit. It costs Sh4, 000 at this pharmacy. But according to insiders in the regulatory authorities, the cost per kit should have been less, ranging between Sh1, 000 and Sh2, 000.

You might have come across the same message, alerting you to access HIV self-testing services at drug outlets located in areas such as busy bus stations e.g Makumbusho and several other pharmacies in the city.

The initiative is aimed at investigating the possibility of making the HIV self-testing kits commercially available in retail pharmacies across the country.

One of the things being looked at is whether people can afford the kits. But in this aspect, it appears some pharmacies could cash in on public ignorance about this pilot process to make money. Hence, the pricing is somewhat variable and higher than recommended.

However, people are willing to pay in other areas, according to researchers who studied the sales and pricing of the kits at 26 local shops in Shinyanga Region. Given the circumstances, the pricing has to be looked at keenly in the due course, by considering factors that motivate the retailers to sell the HIV self-testing kits and how that aligns with public health priorities.

What does the self-testing kit look like?

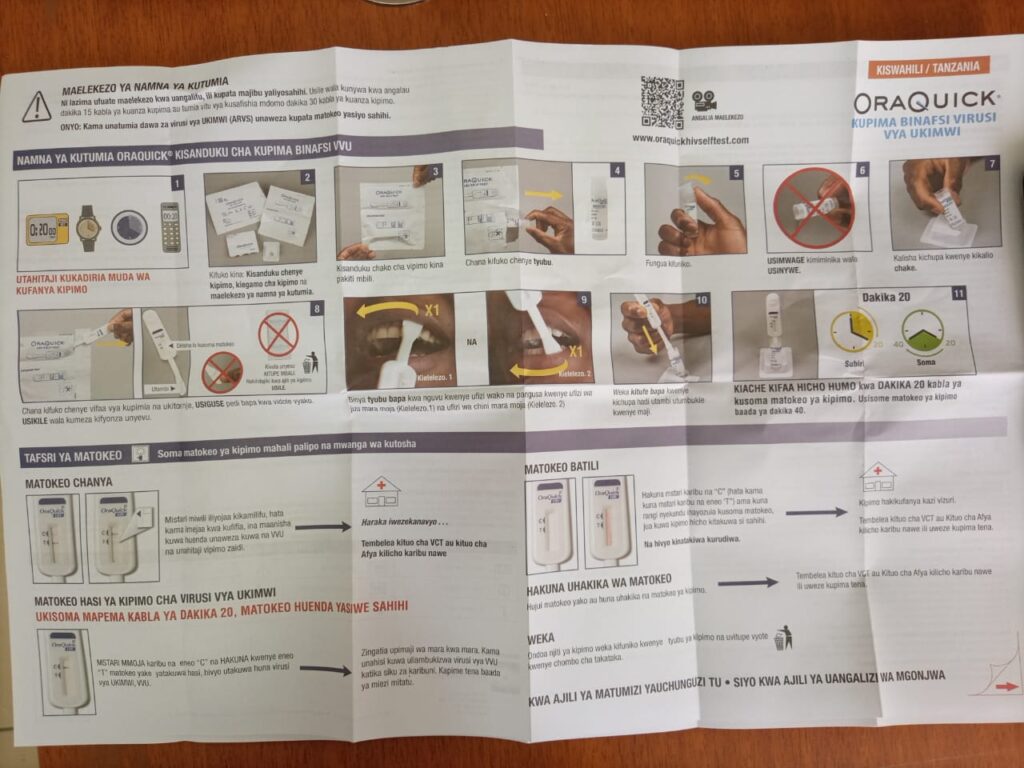

When you go to the pharmacy, the kit comes in the form of a sachet, composed of a test device, preservative, test stand, developer solution vial as well as instructions for use (written in English and Swahili).

No further instructions or counselling were given, unless after asking. No health education. The dispenser insists to the client that the instructions manual is provided alongside the kit.

While it remains to be seen how people will eventually adapt to this new tool, the need for public awareness on self-testing is apparent in the coming days. In the ongoing pilot project, there might be a lot to learn from the process.

A few months after the law was passed to allow self-testing in 2020, researchers raised concerns about circumstances surrounding an individual who decides to self-test. One may ask, who gives this person counselling before and after self-testing?

There is also a risk of suicide after seeing HIV positive results, and another risk of coercive testing of a female partner or associated intimate partner violence. What happens after this person has tested positive and how is s/he linked to care?

Please note, that self-testing does not confirm your HIV status, so, whether you get positive or negative results, you are required to go to a designated health facility for further check-ups. Literally, this means that you still have to go to the health facility as a new client, despite having self-tested.

During self-testing, there is a risk of inaccurate test results. What happens in situations where a person (who may ignore or is unaware of some important SOPs) reads the results after 10 or 20 minutes instead of the prescribed time?

In a recent encounter at the big pharmacy in Mwenge, Dar es Salaam, the dispenser was keen to say, “During self-testing, make sure you check the results in 5 minutes, not beyond that.”

If you visit the pharmacy to get the kit, there might be little guidance. You can actually be given the kit as you want it.

Then, off you go.

You can test yourself at home, office or any other place that has the privacy you need. Some people have previously complained about the lack of privacy when they went for an HIV test. With self-testing, no more queuing at Voluntary Counselling and Testing (VCT).

And it’s legal to do that.

Two years ago, Tanzania passed a law to allow self-testing for HIV. “So now it is official in Tanzania for a person to self-test for HIV,’’ said Ummy Mwalimu, the Minister of Health on 20th December 2020. “These kits will be sold in shops, as well as free distribution in some areas, because sometimes people may feel too stigmatised to access them for self-testing,” said Mwalimu, ushering a new era in HIV testing in Tanzania.

Evidence shows HIV-self testing is feasible in Tanzania. The kits have been distributed in selected pharmacies in Dar es Salaam, Mwanza and Dodoma or you can access them free of charge at designated testing centres.

If the kits are officially left to be commercially available countrywide, it is expected that the burden on healthcare workers who are already constrained by many tasks at various testing centers and health facilities could be reduced. This might save time for other social and economic responsibilities.

What’s more? Could this address the concern that men have been holding back the country’s efforts to ensure every Tanzanian goes for an HIV test? Possibly it could, given the amount of evidence available. But there has to be more innovative ways of increasing men’s uptake of the kits.

“…distribution of HIV self-test kits through close male friends could improve the proportion of men reached with HIV self-testing services and improve HIV testing rates in this population where uptake remains low,’’ a study done in Dar es Salaam suggested last year.

But who sets the criteria for HIV-self testing in Tanzania? And, how supportive are health systems for this new product and self-service?

Since self-testing is not to be taken as confirmatory, it shouldn’t be problematic for people to get confirmatory tests when the product officially rolls out, hence the need for investment in biometrics, phone applications, call centres and a centralized database.