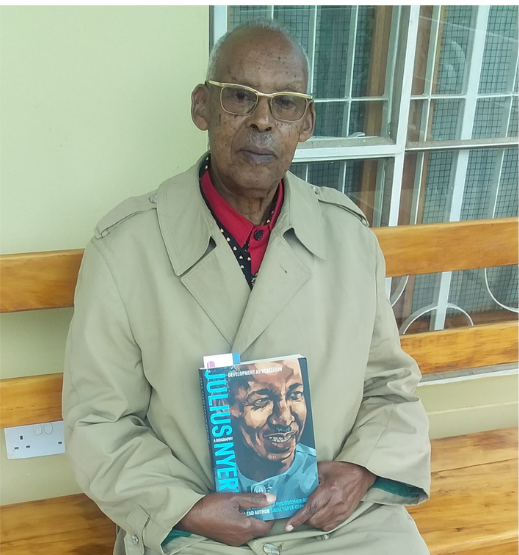

At the age of 91, Callixte Twagirayezu would be mistaken for a person a bit younger than his actual age. He has the natural wrinkles of an old man but, he hasn’t slowed down yet. He has endeared himself to a livestock farm in Kamachumu, Bukoba where he’s spending his retirement after 50+ years of working as a medical doctor in his region. As an ordinary person and devoted clinician, he has witnessed pandemics, tackled some and managed to survive to this old age.

“When I turned 80, I told my children that I no longer want to work. I became tired and wanted to take care of my home,’’ says the retired medic, who exudes charm and charisma as he speaks. His old age aside, Dr.Twagirayezu, as he is popularly known in Bukoba, is an alumnus of Lubumbashi University in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He harbours a unique story as a medical doctor who, at first-hand, diagnosed Tanzania’s first three patients of HIV in 1983, when many were still in the dark about the disease.

Twagirayezu speaks to MedicoPRESS at a time when Tanzania and the rest of the world are yet to end the COVID-19 pandemic that has killed millions and ravaged economies but memories of the HIV/AIDS pandemic which occurred about 40 years ago, still linger in his mind. He recalls vividly, how he was jolted into action after noticing patients with an unusual pattern of symptoms. And how he followed them up and made friends with them as part of the job. In fact, he’s still in touch with a living HIV patient who was diagnosed in 1985.

The puzzling two men, one girl

Sometime in early1983, at Ndolage Hospital on the beautiful highlands of the West of Lake Victoria, Dr. Twagirayezu, by then the Medical-Officer-In-Charge and his team, admitted three patients: two men and one girl.

“One man had symptoms of tuberculosis. But tests could not confirm the disease. Another one looked like he had a sexually transmitted disease that had been mismanaged. The girl had diarrhoea but we couldn’t tell what disease she had, after running all tests,’’ says Twagirayezu, curtain-raising a story of the famous three patients who would later become a reference point to how the viral disease was first detected in Tanzania.

“We were confused by the three cases,” Dr. Twagirayezu recalls. However, two years earlier, United States had already reported “acquired immune deficiency syndrome” as a clinical condition among five patients from gay communities. But still, for many countries, such as Tanzania at that time, the realities of such a disease were still far-fetched.

Then, at the Lutheran-run Ndolage Hospital in Kamachumu, Kagera region, the reality was beginning to unfold. Tanzania was reeling from the War with Uganda. On the ground at a local hospital, in the midst of a dilapidated health system, Twagirayezu and his team were busy guessing after receiving the mysterious three patients. In search for answers, Twagirayezu remembered a Swedish doctor whom he had previously worked with at Ndolage and still in contact via letters.

“I wrote him and explained our frustrations on our patients who were deteriorating day by day,” he tells MedicoPRESS.

In response to the letter, the doctor sent me a medical journal, The Lancet, with a note on top of the journal inscribed “Read page 121 you might find answers.”

Twagirayezu then read the article to his fellow doctors about a disease documented in the U.S and reportedly already in Europe. Reasons for the disease were still unknown by then. It was referred to as ‘acquired immune deficiency syndrome.’ “It was not known whether the disease was caused by bacteria, virus or anything. The most affected people were young.”

He officially presented the article in the following day’s clinical meeting and was convinced that the three patients were victims of the same disease explained in The Lancet.

It was towards the end of the year. In his end of the year report to the Ministry of Health, he also included all the information about the three patients and the facts gathered from The Lancet in regard to the new disease. Some few months passed and the world confirmed that the disease was caused by a virus. Scientists could detect it in the affected human blood. The Swedish doctor sent some reagents to Dr. Twagirayezu to test the patients in Tanzania.

“We tested and confirmed that it was the virus. The test was first done at Ndolage,” he says, while demonstrating a sense of relief, that finally, it had been unravelled.

Interest in HIV/AIDS

This made Twagirayezu develop interest to know more about the disease and find out how it was spread. He turned to the girl he had diagnosed and asked if she was married.

“She told me she was not married but had a lover who lived in Nshamba (Bukoba). I made it a habit to pass by the shop of her lover, to make some follow-ups without the knowledge of the man. He became sick after seven years.” By that time, the girl I diagnosed had died.

When the man reported at the hospital, Dr. Twagirayezu asked him if he knew her (by name). “He confirmed to me and admitted that she was his concubine. The businessman was diagnosed with the same disease as his late concubine. There were no ARVs at the time. The man succumbed to HIV/AIDS soon after becoming sick. That gave me a hint that the disease’s incubation could be up to ten years and that within that period, an infected person could spread the virus.”

It is the same interest that has made him to track one HIV positive man who he knew since 1985 before the advent of ARVs. “The wife died some years back but he is very fine up to date in Bukoba town. He is my friend,” says Twagirayezu.

HIV/AIDS amid weak economy, low technology

HIV/AIDS hit the country at a time when Tanzania had just emerged from the war with Uganda. The economy was weak. Technology was low. Dealing with a new disease was another burden. “We embraced palliative treatment,” he says. Here he quoted his medicine teacher back in the years who told them: “Sometimes you will cure your patient, very often you will make their life acceptable…but try always to console your patient,” he remembers. Apart from consoling patients, they also tried to provide all necessary advice such as not taking excessive alcohol, working moderately, eating well and avoiding multiple partners.

Panic, just as with COVID-19

Given his age, Twagirayezu says he keeps away from hospitals and gatherings and has been educating himself through medical journals about COVID 19 since it emerged in China in late 2019.

“Like what we have seen during the COVID 19 pandemic, people also panicked and were shocked when HIV/AIDS first emerged. Being mostly sexually transmitted, the Haya people used to say ‘Ekwete habi, neija kutumara’ meaning they feared the disease had targeted a risky aspect of their lives and would finish them all. But, he says, “Surprisingly, later people got used to it and life continued.”

Misinformation surrounding HIV/AIDS was not spreading as fast as it is doing in the current era of advanced communication systems. During the HIV/AIDS era, people accepted that there was a new disease and they learned how to prevent it from spreading. The predominant talk among people at that time was about the origin of the disease. The absence of social media and citizen journalism during the HIV/AIDS era is what differentiates it from the COVID 19 when it comes to myths and misinformation, he explains.

How the virus came to Tanzania

It is not exactly known how HIV entered Tanzania, but it is believed that it came in via the neighbouring Ugandan boarder. After the war with Idi Amin in Uganda, economies of both Tanzania and Uganda were shattered. There were not enough essential goods and products. Rukunyu village in Nyangoma, Kiziba division, Misenyi district in Kagera region along the Tanzania-Uganda border used to be a large commodity black market where people from both sides traded.

“There was a lot of contacts among people at this point,’’ recalls Dr. Twagirayezu. “When people became sick in Uganda they used to say their colleagues on the other side of the border had bewitched them because of their business; the same happened on the side of Tanzania.”

‘Juliana’ and ‘Silimu’ were the names

In 1980s, a person who became sick from HIV/AIDS was referred to as suffering from Juliana or Silimu. Both names came from Uganda. Juliana was a fashionable women clothing at the time and “it happened that the fashion from Uganda came at the time when had HIV/AIDS erupted. So, people related the clothing to the disease,” explains Dr. Twagirayezu. ‘Silimu’ was borrowed from an English language word ‘Slim.’ It came to be popular because majority of patients would lose weight and appear so slim.

Who is Twagirayezu?

He was born on 1st August 1931 in a grass thatched house at Sovu village, Butare in the Southern province of Rwanda. His father who studied up to standard five had made it a habit to wait outside the grass-thatched house when all his children were born and properly kept their records. He was born to Dismas Ruchogoza and Paskazia Kanziga. He began attending a Catholic-run primary school in Butare and later moved to a government school run by the Belgian Freres de la Charite (Brothers of Charity) at the same place in the.

“We were shepherds. Many children did not like school at the time. Those who agreed to go to school, were given five cents every week,” he recalls. Five cents was a lot of money to pay for farm labourers, so many parents transferred their children to the government school. He finished primary school at the age of 12.

He went on to secondary school run by Brothers of Charity. It was the only secondary school for Rwanda and Burundi at the time. “The competition was intense. The school took 40 students from Rwanda and 40 from Burundi. They filtered poor performers every year,” says Dr. Twagirayezu. He was one of only 40 students to complete secondary education.

Becoming a medical doctor

After high school at the age of 17 they had the choice to join the fields of agriculture, administration, medical science or veterinary science. He enrolled in medical science. According to the Belgian system, he studied four years of theory and two years of practice and obtained a diploma. There were 11 who completed the training; 10 Rwandese and one Burundian.

Due to a limited number of Burundians who completed medicine that year and since Rwanda and Burundi were one under colonial rule (Ruanda-Urundi), Dr. Twagirayezu was sent to serve in Burundi for two years of practice and returned to Rwanda for final exams. He officially began work in Rwanda from 1954 to 1958.

Ndolage, Kagera

The year 1959 saw ethnic violence in Rwanda. This forced Twagirayezu flee to Uganda. He did not stay for too long and went to Zaire, now known as Democratic Republic of Congo and then lived in independent Burundi where he worked for a year until 1961 when he received a scholarship to study medicine at Lubumbashi University.

“It was like a fresh start, I studied medicine again for four years. I only had a year cut,” he says. He returned to Burundi again but because of political instability, he started looking for work elsewhere.

In 1964, from Burundi, he went to Ndolage Hospital in Kagera region to ask if they wanted a doctor. They agreed and was asked to present his certificates that were sent to the French embassy in Dar es Salaam for interpretation.

“The Ministry of Health at the time took a whole year scrutinizing my certificates. The government of Tanzania wrote letters to the schools I attended in Rwanda and Congo to verify the validity of the certificates,’’ says Dr. Twagirayezu. In 1965 he was officially accepted to start work at Ndolage Hospital where he worked until his retirement in 1991. Dr. Twagirayezu worked at Ndolage Hospital for 26 years. Out of that time, 12 years of service he was the in-charge of the hospital.

He then worked for a French organization called Medecins Du Monde (Doctors of the World) for another 12 years in Bukoba town. In 2004-2012 he worked for an Orthodox-run hospital in Bukoba and later decided to take a break and concentrate on farming.

Notable successes

“When I meet happy people reminding me how I helped them out during my days at Ndolage I take that as a great success.” He says he treated many people in Kagera region who know him and “I am happy that they remember me for the good things I did to them and not bad things. I travelled and lived in major cities in the world, I am satisfied with the quiet village life today living happily with others. I did not get rich but I am not poor,” he notes.

Advice to doctors

Dr. Twagirayezu remembers his anatomy lecturer back then in Rwanda who cautioned his class of 12 that: “Never expect to become rich in the medicine profession, however you will live a happy and dignified life.”

To young doctors he says: “If you have decided to become a medical doctor, always stick to the Hippocratic Oath.”

Edited by Syriacus Buguzi, guided by MedicoPRESS Editorial Policy