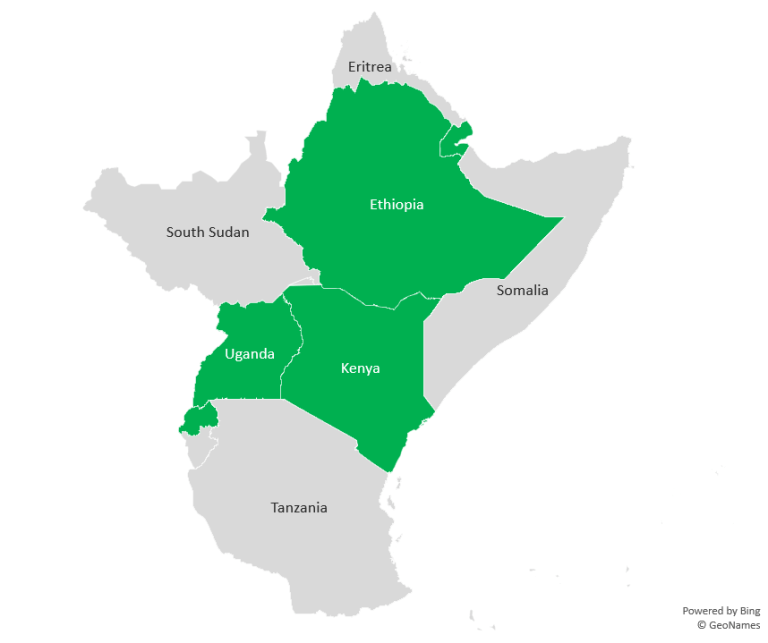

Recently, as countries commemorated World Malaria Day, there was an emerging controversy in East Africa on the safety of bed nets used in the fight against malaria—news was beginning to spread very fast, following claims that the bed nets—treated with synthetic insecticides made from pyrethroids—were were unsafe.

Apparently, news broke in Kenya last weekend, suggesting that Dr Festus Tolo, a researcher at the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) had found a high risk of cancer and asthma to children in the synthetic insecticides, as per a study quoted by Daily Nation newspaper as: New BioMedical Uses of Kenyan Grown Pyrethrum.

Read: Kemri finds use of mosquito nets unsafe

This was disturbing news, especially to the public in the region, given that governments and various health stakeholders have—for many years—been promoting the use of Insecticide Treated mosquito Nets (ITNs) in the fight against malaria—a mosquito-borne disease known to mainly affect children under age of 5 and pregnant women.

Thankfully, the debate—mainly fueled by media reports in Kenya and a section of social media in Tanzania, has somehow been “arrested”—and the dust has of late settled.

Read: Tanzania Scientists Explain Why Mosquito Net Treatment Safe

However, this scenario has left more questions than answers regarding how journalists and researchers in the region should be working together to better inform the public on any new scientific findings.

Dr Tabitha Mwangi, a Kenyan expert in malaria epidemiology believes, “this episode is not good for health communications,” as she alludes to the bed nets debate and the Kemri saga; in a recent article on her personal website, titled:“Treated bed nets – it’s a lifeline not a threat.”

Dr Mwangi argues, “Scientists will be scared of talking to journalists. I am without doubt that the KEMRI scientist [who was quoted by the media in Kenya]…said something that was misinterpretated.”

Medico PRESS is informed that KEMRI has since refuted the claims said to be made by Dr Tolo but the institute has admitted—in a press release—that the pyrethroids at the centre of the debate are generally known to be harmful, although it cautioned that the levels of concentrations of the substance, used in manufacturing bed nets were “completely safe.”

The Head of malaria control unit in Kenya, Waqo Ejersa was quoted by Kenya’s daily newspaper, Nation, as reaffirming the safety of the nets, noting that Dr Tolo was misquoted on the bed-nets saga, and “regrets the information appearing in the paper.”

Because of scenarios like this, argues Dr Mwangi-the Kenyan malaria epidemiologist, saying “…KEMRI and MOH are likely to put even more restrictions before scientists/healthworkers talk to journalists,” in a piece in HealthKenya.

She says, “Having worked in research institutes for over a decade before starting as a freelance science writer, I know how scared scientists are, of being misquoted. I also know that writing under tight deadlines [on the part of journalists] is not easy and a sensational story sells.”

“Above all this,’’ she says, “…doubts have been planted in people’s mind about the intention of giving Insecticide Treated bed nets in malarious regions. My fear is that when such articles appear in respectable newspapers like the Daily Nation, people take them seriously – especially when the person quoted is a researcher at the reputable Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI).”

“The thoughts that are likely going through people’s minds are: ‘Why is there no agreement between the KEMRI scientists – why were they not speaking in one voice – is there something we need to be told that is being hidden from us. Kuna kitu?”

“Truth is – there is no agenda…” argues Dr Mwangi, and warns, “To raise scary fears about treated bednets at this point in time is totally counterproductive and extremely irresponsible… a half-digested untruth can lead to more serious unfounded rumours and put malaria control in jeopardy.”

Dr Mwangi appears convinced that the information on bed nets shouldn’t have caused this furore in the region, if not for media reports on the findings, going by her comment, “I am without doubt that the KEMRI scientist said something that was misinterpretated.”

But Dr Mwangi is not alone in this blame game. For many years, journalists and research communities have long had an uneasy relationship.

Researchers have always criticised journalists for exaggerating research findings based on a small amount of data while important science and research developments are left out.

But on the other side, editors at media houses argue that research findings lack news value and are not packaged correctly while the academics charge the journalists of only being interested in shiny bright objects, writes Rayyan Sabet-Parry, a digital media consultant with UNICEF Innocenti, in his article: “Can researchers and journalists find a common language?”

This conflict between research scientists and the media became a reality in Tanzania, December last year, when Dr Mwele Malecela, former Director General of the National Institute for Medical Research (NIMR), lost her job just a day after she talked to journalists at a press conference.

Dr. Malecela, now working at the World Health Organisation-Afro in Brazzaville, Congo, narrates her incident of how she unceremoniously exited out of NIMR, as she speaks in Geneva during an exclusive interview with a Tanzanian newspaper, The Citizen.

Dr Malecela recalls, “…we were at the meeting[in Dar es Salaam] where so many diseases were discussed—we talked about the Ebola vaccine, the HIV vaccines and a wide range of things…but the journalists just decided to blow Zika out of proportion. Then, at the end of the day, someone [actually Dr Malecela] lost their job.”

Read: President Magufuli fires NIMR boss

Dr Malecela says, “Right now[in Tanzania], there is almost [something] like a “freeze”—of [researchers]…not wanting to speak to the media because of the feeling that what they speak might be misconstrued and at times taken out of context.”

It’s here that Dr Malecela suggests, “Without investment into how journalists work with researchers, it’s going to be difficult for researchers to work with the media.”

“I think, at this point, as a country[Tanzania] we need to build the skills of our journalists to be able to report certain fields through specialization. Let’s make journalists that report on science, technology, medicine and so on. Without this kind of specialization, we are always going to have problems with the media.”

But, can Dr Malecela’s suggestion be a panacea to the problems caused by the gap between research scientists and the media? How best can the two professions engage? Who can best intervene to bridge the gap? Medico PRESS calls for your suggestions and comments on this.

Meanwhile,Tips for researchers and journalists: Before all this investment can be done, here is what researchers and journalists can do, according to Sabet Parry the digital media consultant for UNICEF Innocenti.

For researchers:

- Become familiar with the day-to-day challenges and pressures of news reporting in today’s world.

- Become active on social media. This is where the media community gathers and provides a direct line of communication with them.

- Start bloggingto widen your circles and instantly connect with important streams of discourse anywhere in the world.

- Be a thoughtful consumer of news and blogs and identify/follow those who understand data and science.

- Practice translating your research into common language and craft a short pitch, if possible including the scale of potential impact on populations.

- Explain how your research relates to the prominent issues of the day and present your findings concisely. Practice breaking the research down into a few key sentences.

- Reach out to specific journalists by name, not to media organisations, preferably by phone or direct message or social media messaging. Have your pitch ready to go.

- Seek to build long term relations with the media based on trust and respect.

- Research findings may not have the same news value as other stories and they are not to be treated as breaking news stories. Take your time in identifying which media outlets are best suited for the research and how you will structure your pitch.

For Journalists

- Treat any outreach from the research world as a potentially high value news source. Bona fide social scientists are uncovering evidence to reveal something previously unknown or poorly understood.

- Researchers are often deeply absorbed in their data and not always adept at making it understood to everyone. Spend a bit more time than usual and work with them to understand their pitch.

- Understand the difference between single journal articles and systematic reviewsof evidence, especially those using meta-analysis of research literature.

- Look for research that employs randomized control trials, a robust method of defining impact.

- Before deciding that a particular research story has limited news value make sure you understand its place among a body of evidence.

- A single research study rarely proves causation: (“Coffee causes cancer!”) Learn how and when to apply the terms: “associated,” “correlated” and “caused” in reporting.

- Where necessary explain that findings are preliminary, need validation/replication or add weight to a developing body of evidence.

Continue reading medicopress.media on what researchers in Tanzania are doing.