When she was in her early 30s, at the peak of her career as a young scientist, Julie Makani endeavored to do what many had believed was impossible. She dedicated herself to research a genetic condition that many institutions in Africa, including Tanzania, were unwilling to venture into: Sickle Cell Disease (SCD). At the time, she says, there was more emphasis on infectious diseases such as TB and malaria, and the general belief was that the inheritable disease has no treatment, “is rare, and many people with it, die anyway.”

Undeterred by the skepticism, Makani embarked on the pursuit for a cure of the blood disorder whose true burden was largely unknown. She started building partnerships and gradually taking on leadership roles. Throughout her ascent, she was driven by the desire to heal patients enduring the pain from the complications of SCD. She currently holds the position of Associate Professor of Hematology and Blood Transfusion at Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS).

Today, as she recounts her 20-year career journey in the quest for a cure of SCD, she sits in an office of one of the landmark projects—the Sickle Pan-African Research Consortium (SPARCO)—that was born out of partnerships and networks that Prof.Makani and her team have cultivated for nearly two decades. The project started in March 2003 when she was a young scientist taking bold steps to tackle a problem that many didn’t give attention to—but which was costing people’s lives.

“I have lost family members to this disease,” recalls Makani, who was recently awarded a Medal of Merit by the French Embassy-Tanzania during a colorful event in Dar es Salaam to recognize her dedication to improving clinical care for patients with SCD and the tireless search for a cure of the condition. The National Order of Merit award is one of the many accolades she has received over the years. However, it is the contribution of her scientific work on improving people’s lives that is her highest achievement.

How it started

“The Sickle Cell program started as a research study funded by Wellcome Trust to describe the epidemiology [of the disease],’’ says Makani who is turning 53 this year.

She attributes the success of the program to the approach they used as a team to integrate the research into coordination, healthcare, advocacy and training. “This holistic approach proved to be effective.”

Challenges and lessons

But her efforts to make the integrated approach take root in Tanzania’s healthcare system and practices, are yet to pay off, a challenge that she cites as one of the ongoing hurdles she and her team face.

“Within our field we need to work harder towards an integrated approach. As healthcare professionals, we work in divided quarters and are able to provide services in our specializations but the failure to come and work together causes delay and inconvenience to patients who need to receive urgent care.”

“We all ultimately aim for the same result, which is to serve and improve the quality of life. Imagine if we all came together,” says Makani. She is reflective but also carries a sense of hope, especially when she looks back and recognizes the strides that the Sickle Cell Program has made over the years.

“The program was able to establish one of the biggest cohorts of Sickle Cell Disease patients in the world, with enrollment of over 5000 patients,’’ she tells MedicoPRESS, further explaining the project’s contribution to improving the country’s healthcare system.

“We have been able to expand from having just one pediatric clinic at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH), which was the only dedicated Sickle Cell clinic in Dar es Salaam, and other patients were only seen on Fridays at the haematology clinic.”

“Currently, there are Sickle Cell clinics at the main referral hospitals such as MNH and Aga Khan Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Bugando in Mwanza, Mnazi Moja in Zanzibar, Benjamin Mkapa Hospital in Dodoma and more in other regions – the growth has been incredible” says Makani, who has surmounted barriers in her push for better healthcare services for patients with SCD.

The condition is now known to fatally affect an estimated 10,313 children with SCD aged below 5 years in Tanzania every year—statistics that Makani reflects on when “seeing the number of patients and people with sickle cell disease who have died, and all who have had complications,” as she believes that, “more could’ve been done for them, it is an improvement that we are working on.”

But the proudest moment for Makani is that the disease that was previously side-lined is now getting the attention of policymakers and key stakeholders as “a priority condition among Non-communicable Diseases in Tanzania, in Africa, and globally.”

“[Our program] has initiated transplantation services, something that was not previously available. These efforts were further complemented and completed by the Muhimbili National Hospital. Despite that these efforts do not specifically target transplantation for Sickle Cell Disease patients, we are glad that we have been part of making transplantation services in Tanzania available as other African countries like Nigeria and South Africa have done.”

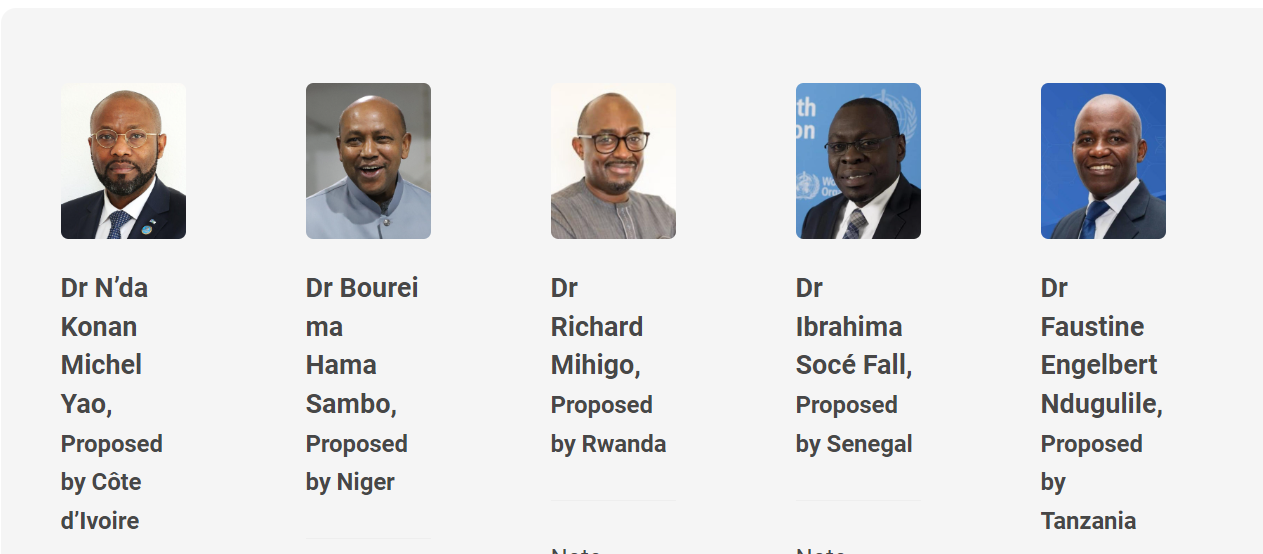

Prof. Makani’s efforts have also led to the creation of patients’ organizations and advocacy groups around Sickle Cell Disease. One of the people who has benefited from Makani’s program is Arafa Said, the founder of the non-governmental organization, Sickle Cell Disease Patients Community in Tanzania. Ms. Said, who is also a survivor of SCD won the Global award for International Sickle Cell Advocate in 2017.

From one haematologist to 30

In terms of research and education, Prof. Makani says, “great achievements have been made in the creation of more specialists in haematology. We started with one hematologist in 2003, and now we have at least 30 hematologists. At postgraduate level we train specialists and super specialists and at undergraduate level we provide training in hematology and blood transfusion to a range of future healthcare providers such as doctors, biomedical laboratory scientists, nurses and pharmacists.

“In addition, we also conduct trainings of healthcare providers in short courses, or seminar trainings as part of continuing the provision of education on Sickle Cell Disease.” Prof. Makani emphasizes that raising awareness and providing education on sickle cell disease contributes to reducing stigma around the disease and positively contributes to the lives of those affected by SCD.

Her sacrifices

What keeps Makani focused on success? Her uncompromising values.

She tells MedicoPRESS that her work has involved making sacrifices but that it is worth it.

“I work very hard which has led to an imbalance in other aspects, but I am guided by values of diligence and commitment and I am grateful for family, friends and colleagues who are supportive of the work I do. I would do it all over again if asked to,” she says, with emphasis on how her values and support have also helped bring hope to thousands of patients and their families who are affected by SCD.

She commends the government on the improvement of Sickle Cell screening not only in newborns but also point of care tests. “It is a commendable effort made by the Ministry of Health in many health care facilities.”

But she stresses the fact that New Born Screening (NBS) has to be a top priority. “We need to be able to say, I have screened, I have identified a disease, and these are the services we will provide going forward so that it is part of a continuum of care and health care services.”

She adds that, “clinical services shouldn’t be just about providing prophylaxis like penicillin or supplements like folic acid, but also providing disease modifying agents like hydroxyurea. Clinical services should also give patients the options of curative services such as, bone marrow transplant and gene therapy.”

Prof. Makani elaborates on the importance for countries in Africa to be able to build a healthcare system where all the elements of health care are made available for the patient, from screening to achieving curative results. She believes that providing quality healthcare is a commitment to the philosophy that healthcare systems adhere to, which is to save and improve people’s lives.

Message to young people

To the young generation who aspire to be researchers and scientists, Makani says “I strongly encourage them to join and expand on the research in Tanzania as there is a need for solutions and so much room for innovation.”

“I would say learn from my weaknesses but also mimic my strengths and largely improve on them.”