For many years, Tanzania has endeavored to tackle challenges related to Human Resource for Health (HRH), however, the emphasis has been on increasing the number of doctors and therefore flooding the market with medics as a way of curbing shortages across the country.

The question that now begs an answer is: has the approach worked to improve the HRH? Does increasing the numbers still matter anymore?

Looking at the growing numbers of doctors, one may say “yes, much has been done,” proof of this being the many doctors out there on the market who have not been recruited in government-run health facilities for a long time.

Read: Tanzania trains more doctors than it can employ: study

However, the irony is that district hospitals, as well as other lower level health facilities continue to suffer an acute shortage of medical doctors. Where are we missing the point as healthcare planners and policymakers?

Well, Tanzania is operating in a decentralized healthcare system that was introduced in the 1990s. It involves the transfer of functions, power and authority from the central to the local government authorities (LGAs), with the aim of bringing services including health closer to the people.

It wasn’t a bad idea to introduce this decentralization system, especially when it comes to handling the HRH. But, look here! Recruiting doctors to district hospitals and leaving it to the local government authorities who are financially incapacitated, brings with it another big challenge.

If, for instance, doctor A is in district Y, and he/she is receiving housing and on-call allowances on time, yet doctor B who is in district X is not receiving an equal opportunity for the allowances, then it means that the latter (doctor B, in district X), will not be equally motivated to stay in his/her district.

This is a sad reality that we found on the ground in three districts that we surveyed over a period of 9 months in Tanzania. From complaints of lack of house rent, a hostile working environment and lack of career development, the medics disclosed to us why they were intending to quit district hospitals.

Read original study: Retention of medical doctors at the district level: a qualitative study of experiences from Tanzania

Medical practice or providing medical services is a calling. However, the choice of working in a hostile environment, with less resources and without motivation, is a tricky one. Data show that 75 percent of the people live in rural areas, however, only 26 per cent of the country’s doctors serve in those areas.

Since the number of doctors being produced annually in the country is high, yet many district hospitals continue to “starve”, it’s clear that key interventions are needed.

There is a growing need for much wider stakeholder engagement in training, deploying and retaining them in district hospitals. The later, of course, requires huge investment. Key aspects must be looked at.

Unfavorable working conditions

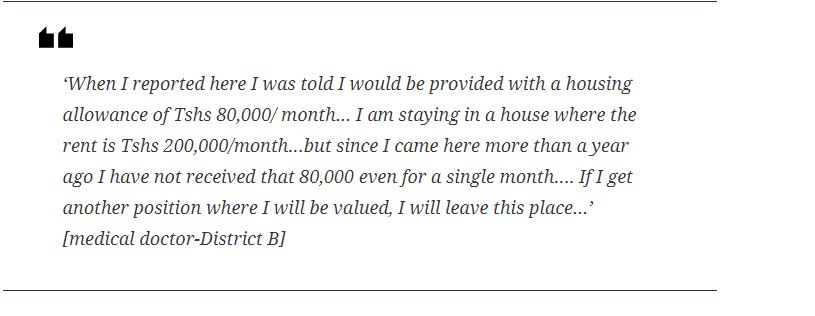

In district hospitals, there are medical doctors (MDs), who are contemplating of migrating from one district to another where financial incentives are paid on time. During our survey there were cases where the doctors complained that allowances are delayed for more than a year.

What about centralizing the doctors’ incentive packages? Is it time to create a comprehensive package that will either be financed centrally or the district authorities? Through this, I do believe, the doctors can be motivated. And, to ensure that it works out, the district authorities should be held accountable for failing to implement it.

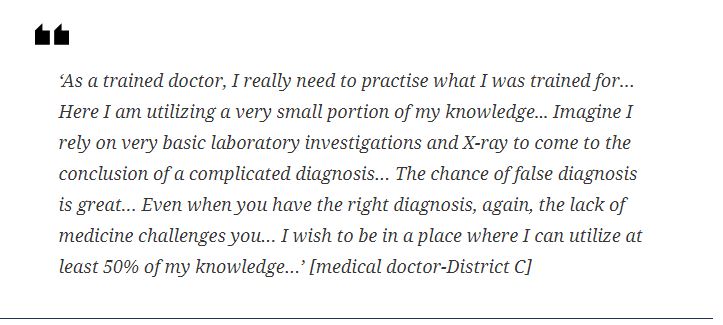

Under-equipped hospitals

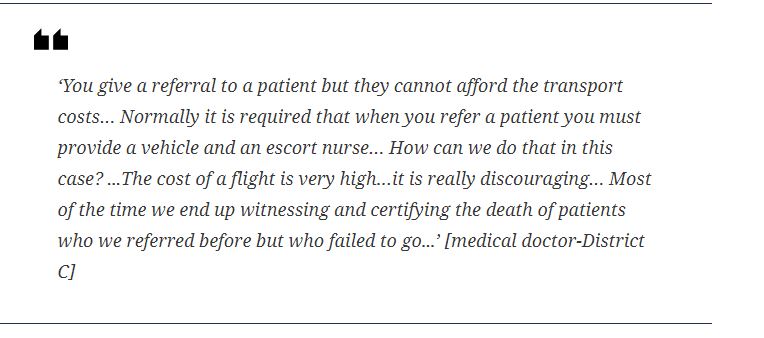

Some hospitals lack reliable means of transport to carry patients to higher facilities for referral healthcare. Doctors, in one of the districts surveyed, stated that their facility was underequipped to an extent that it was discouraging them to stay on, and hence their intention to leave.

In one of the district hospitals, a doctor echoed the difficulties faced in attending to patients that were in critical condition. Some of these patients had been referred to higher-level facilities but failed to go due to the absence of reliable means of transport. This, according to them, caused dissatisfaction and discouraged doctors from staying, hence their intention to leave.

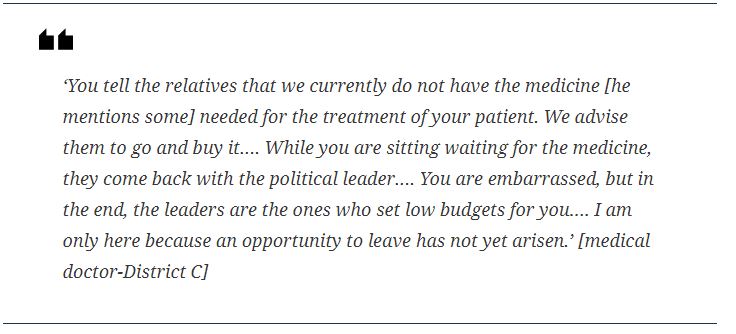

As this happens, the government has been devising various ways of ensuring that doctors work in rural parts of the country; including district hospitals. These may work better if health services are boosted and that political leaders get on the frontline in supporting the change.

During our study, it was reported that some political leaders were, instead complaining about poor health services in district hospitals even as they knew of the financial challenges faced by the health facilities.

But, what about career development?

In an effort to boost the doctors’ career development, two of the three district hospitals prepared written career development plans. This was found to help districts to budget for their annual implementation. One of the managers explained why it was important to create such incentive packages.

Some other managers have gone the extra mile to create opportunities for the medical doctors to earn extra income but still be retained at the district hospitals.

Realizing that some doctors cannot be retained in district hospitals because of lack of extra income, one of the districts surveyed by the researchers came out with an arrangement to open a private practice within all its hospitals but there were no similar arrangements in other hospitals.

In general, we need to get at the crux of the problem by creating an environment for retaining the doctors. In this case, a centralized monitoring system for the doctors could be helpful in reducing the early departure from the district hospitals.

There is growing need to review the way the doctors are trained, deployed, rewarded, monitored, and how to hold them accountable. But, priority is needed in making sure that when they are posted to their workstations, they find safety, late night staff transport and standard housing.

Great Dr,

We need Drs for diagnosing and treatments, but the problem comes on payments. According to the revenue collection per year it is difficult to tackle this problem. Remember here we are talking on healthcare but the same problem is on education, magistrate in general all miniseries. What is needed is patriotism. The government can’t tackle this problem abruptly. Let Drs be empathy, loving, trustworthy and instruments of God.