The largest-ever data set of malaria prevalence in sub-Saharan Africa has revealed a long-term decline of the Plasmodium falciparum(a malaria causing organism) in sub-Saharan Africa since 1900. The study was published Wednesday October 11 in the Journal Nature.

Lead Author, Professor Robert Snow of the Kenya Medical Research Institute in Nairobi and his colleagues gathered data from the past 115 years on the prevalence of malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

Findings include results of 7.8 million blood samples collected across almost 37,000 locations in 43 countries, including Tanzania.

The 115-year history shows that malaria in Africa is still complex and predicting the future of the disease based on climate or economic development alone would be foolhardy.

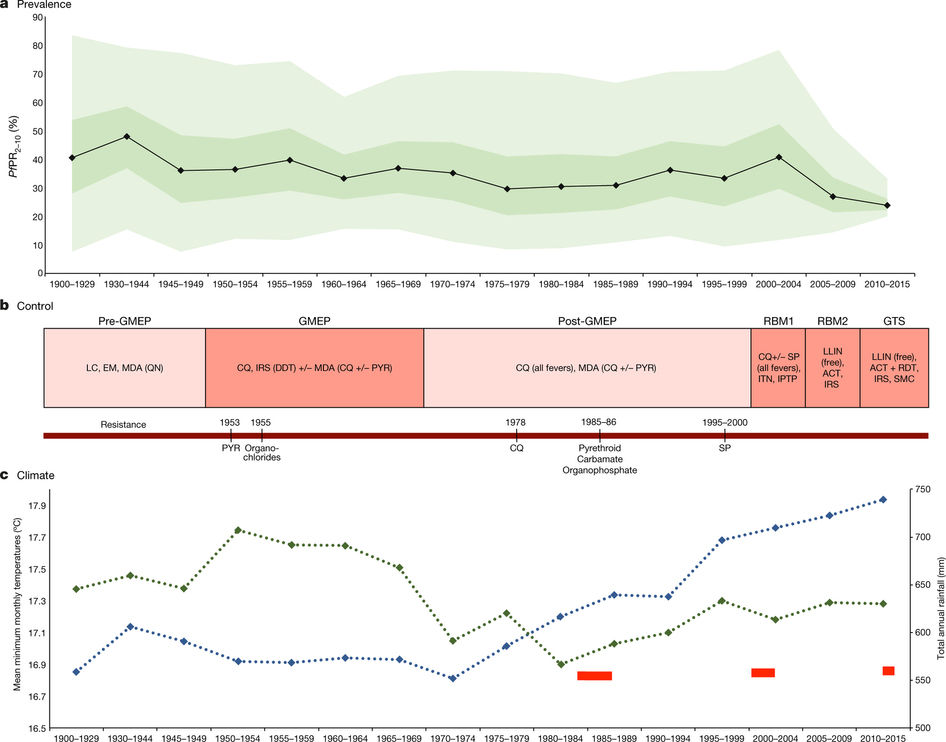

The research team found that the malaria infection rate has generally declined in sub-Saharan Africa, from 40% of those examined in 1900–29 to 24% in 2010–15.

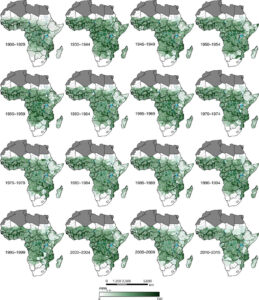

The researchers analyzed the data to estimate malaria infection prevalence for each of 520 administrative units of Sub-Saharan African Countries and Madagascar for 16 time periods since 1900 through to 2010-2015.

There were two periods of rapid decline in infection, coinciding with the introduction of two major anti-malarial compounds between 1945 and 1949, and the widespread introduction between 2005 and 2009 of bed nets treated with insecticides and a new combination drug treatment.

Resurgence of the disease between 1985 and 2004 can be attributed to the spread of drug resistance, unusual weather events and a lack of investment in prevention.

The team notes that large areas of West and Central Africa still experience high rates of malaria transmission, and warn against crediting the most recent decline in malaria prevalence to human intervention alone.

Professor Snow says “People often focus on recent history in tracking malaria in Africa, to inform donors and control programmes on recent actions. The longer history of malaria in Africa allows us to put into context the recent decline.”

Co-Author Abdisalan Noor adds “Shown in context, the cycles and trend over the past 115 years are inconsistent with explanations in terms of climate or deliberate intervention alone. The role of socio-economic development, for example, remains poorly understood”

The study reveals that the biggest historical drops in malaria followed the Second World War with the discovery of DDT and chloroquine; and then in 2005 with the rolling out of insecticide treated bed nets and new drugs to treat malaria.

Malaria prevalence was low during the late 1960s, through the 1970s and early 1980s. This was a period when, despite the international community abandoning investment in malaria control in Africa, chloroquine use was widespread with repeated dosing available to the general population.

Chloroquine resistance expanded across Africa in the 1980s, and in the late 1990s unprecedented rainfall led to flooding and major malaria epidemics. Ministries of Health across the continent woke up to the perfect storm without any significant mosquito vector control in place. Malaria prevalence returned to the levels seen before the Second World War.

It took a further five years for the international community to provide free insecticide treated bed nets and effective malaria treatments.

The financial response by the Global Fund and the technical revisions to policy by the World Health Organization after 2005 led to one of the largest drops in malaria infection prevalence witnessed since 1900.

The findings urge caution the projecting of the future of malaria in Africa. The current prevalence of infection, 24%, is at its lowest in 115 years but gains have stalled since 2010 and 240 million infected individuals remains a substantial burden.

Little has changed in the high transmission belt across West and Central Africa. Emerging insecticide and drug resistance and growing international ambivalence to funding control further increases the risk.

“The history of malaria risk in Africa is complex, there have been perfect lulls when drugs worked and droughts prevented mosquito’s transmission infection; there have been perfect storms when drugs stopped working and flooding affected large parts of Africa,’’ says Snow.

“It has been a history of long term cycles and predicting the future of malaria in Africa based on climate or intervention coverage alone is difficult” Snow further explains.

The researchers urge for new tools for the poor and high malaria burden areas of Africa, a focus on eliminating malaria in the low burden margins of Southern Africa, or small islands across the world or run the risk that high burden countries in Africa being ignored and left behind.